Gendering British Politics

- Daphne Argyropoulos

- Feb 15, 2018

- 9 min read

On Saturday 10th February I journeyed to Cambridge bright and early in the morning to attend their History Masterclass. The train I took was full to the brim with other students my age all congregating over a shared love of their studies which was so exciting to witness!

The day for all the historians, myself included, involved two undergrad-style lectures and an admissions talk/Q&A. The two lectures were Gendering British Politics, given by Dr Ben Griffin, and the second was Nationalism and Independence in Africa, given by Dr Poppy Cullen. Here I will discuss the points made by Dr Griffin and expand on some of his ideas. If you would like to read about the second lecture, click here.

I found it very exciting to listen to a lecture about a topic on which I already knew a certain amount from my History GCSE as it allowed me to be more critical of what I was hearing and to think in more depth about the content of the talk. Also, of course, given that this month we have celebrated the centenary of the Representation of the People Act gaining royal assent it is a particularly apt time to be reflecting on the transformation of gender roles in the last 200-odd years with respect to politics, as was the focus of Dr Griffin's lecture.

He began be exploring what the expectations of men have been and how that has changed over time. In the 17th century, what it meant to be manly was, unsurprisingly, very different to in the 19th and 20th centuries. In the 1600s it was the responsibility of the man to spend as much time as possible at home when he wasn't at work so that he could look after his family. Any man who would go away for extended lengths of time lacked the qualities it required to be a masculine man. However, this attitude experienced a huge shift as Britain began to get involved in more wars. Towards the end of the 19th century, men started to kick back against the idea of staying home to look after their wives and children and what flourished was a trend of military leave and all-male sports. A good example of this is the Order of the White Feather, founded after the outbreak of WW1 in 1914, which was a group of women who would hand out white feathers to men they saw in the streets as a symbol of cowardice to encourage them to join the army. During times of conflict like the two World Wars, conscientious objectors were seen as cowards and as though they didn't want to protect their civilian friends and relatives. This is clearly a stark contrast to the prior attitude that men should stay close to home in order to protect their families. This changed once more after the wars: there was a retreat from the ideal for men to be militaristic as that was now strongly linked to the mass slaughter and destruction of such devastating periods.

Image source: http://spartacus-educational.com/FWWfeather.htm

With this shift in attitude regarding men's involvement in family life came a shift in the ideal personality of a man. Over time, men were expected to be more stoic to show they were emotionally 'stable'. This had a direct influence on the sort of public image politicians wanted to put out in order to seem more electable -- something we notice especially since there were very few women, if any, involved in politics as these shifts took place. Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone made a point of displaying his interest in tree felling as part of his aim to appear more masculine and thus more stable. PM Anthony Eden was very visibly stressed and anxious over the Suez Crisis but his successor, Harold Macmillan (commonly nicknamed SuperMac) was known for being incredibly phlegmatic which the Conservative government was far more comfortable with. PM Chamberlain's approach to the Boer War was his exact projection of the promise of "I swear I'm not effeminate."

The expectations of men also had an influence on legislation as what emerged in this period of change in attitude was a relationship of power between the varying forms of masculinity. One prime example of this is the criminalisation of homosexuality. Another is the Second Reform Act in 1867 which made a clear distinction between good, working men who looked after their families and those who were not good men. The property qualification mentioned in the Act enforced the ideal that men should be financially independent such that they can afford housing -- these were the men who deserved the right to vote. Therefore, those receiving poor relief were not eligible to vote. Furthermore, the privileging of some forms of masculinity over others was clear when in 1918 conscientious objectors were stripped of the vote until 1926.

The trend is the same when considering the privileging of men over women.

However, women were still heavily involved in politics in the 19th century even though they couldn't vote: they were often key members of pressure groups and local government bodies.

Dr Griffin argued that from the 19th to 21st centuries there were three significant transformations in the patriarchal state:

1. Change in what is considered political

2. Change in the nature of the state

3. Growth of party politics

Firstly, women could vote in local elections in the 19th century as this wasn't seen as party political. Local government was concerned with peripheral issues of less importance to the central figures of the party who focussed more on national issues, so education, poor relief and social policy were dealt with by local authorities. Therefore, local government, then less related to parties and more just the needs of the local area, was an acceptable place for women to voice their opinions and actively make an impact.

Secondly, over time the state was changing such that there were more bodies with smaller and smaller fields of interest: in 1870 school boards were established, county councils in 1888, parish and district councils in 1894 and local education authorities in 1902. While women could vote and stand for election in local elections in 1870, as local government was purged and replaced by more specific bodies (which often weren't elected, like the local education authorities established in 1902) women had fewer and fewer opportunities to exercise their right to vote; however, they were able to be members of the new local authorities. By 1900, local government had grown to become 50% of government expenditure. Now that local bodies were so significant, the social issues they were concerned with became issues of the central government, which we saw in practice in the first two decades of the 20th century with the liberal reforms. To that end, women who were involved in local political bodies therefore had a huge role which played into the transformation of the patriarchal state.

Thirdly, in 1867 the Conservative government set up a union for active party supporters which meant that for the first time you could be a member of a party without needing to be an MP or politician of any sort. This was a new chance to decide whether to include or exclude women in politics. As we now know, it was decided to exclude them. With the expansion of politics and the increase in devolution from central government throughout the late 19th century and throughout the 20th century, political parties began to run out of money so they couldn't afford to pay men to complete jobs such as canvassing. This is when women got more involved as they were hired for free to complete this work instead. In 1887 the Primrose League was set up which was a league for both men and women to work for political parties for free. By 1900 there were 1.5million members, over half a million of which were women.

It wasn't until 1918 that individual women were able to join the Labour Party when the Women's Labour League merged with the party. Click here to read a great article on the influence of women on the Labour Party in the 1920s. Labour policies were decided in conferences where voting was done in blocks. This flagged issues for women as if, for example, a labour union had 40% female membership - or any female membership less than half - it more was likely that the union would vote in favour of the men's opinions since they were the majority of the group. In an attempt to rectify this, a women's conference was formed in the 1920s so women could have more of a say; unfortunately, the policies decided at the women's conference weren't binding on the overall party policies which meant this effort fell flat.

While we would argue now that women have far more of a say as part of a party than they did at the start of the 20th century, it wasn't until 1994 that the law stated it was illegal for a man to rape his wife. Clearly, women's rights were not such an important issue in the eyes of the government for a significant amount of time after women became theoretically more involved.

Margaret Thatcher, the first female Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, was turned down from being the Tory candidate in her constituency in 1957 as she was told "politics is no place for someone with a young family." Who ran in her place? A man with four children all under the age of 8.

When Thatcher was eventually elected, despite being an emblem of women's rights, she only appointed one woman into her cabinet. Dr Griffin argued this could lead to a discussion of double standards or the idea that the fight for women's involvement in politics was not a unanimous one. I, however, would argue it was more a matter of there being a higher number of experienced men suitable for roles in the cabinet (though this can circle back to limited opportunities for women to gain experience in high-up roles in politics before this point; I am in no way arguing that there wasn't a deficit in gender equality in politics).

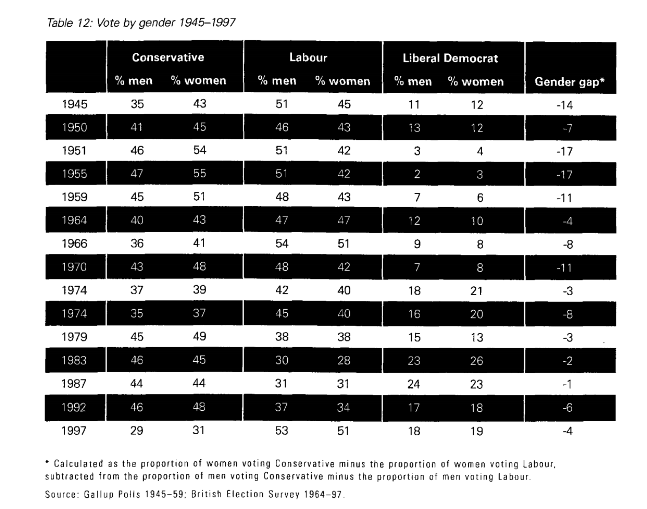

Following the Representation of the People Act's passage in 1918, the Conservatives in particular began to adopt policies to win over the new, very large, female electorate which made up 40% of the total electorate. Dr Griffin then showed us a table of demonstrating the voting behaviour of women compared to men throughout the 20th century similar to this one which I found in another great article on women's political participation in the UK:

The increase in women voting for the Conservatives instead of Labour or Liberal implies that these two other parties were unsuccessful in appealing to women. Post-WWII women were quite biased towards the Tories; Dr Griffin mused that had women not had the vote at this time it was extremely likely that Labour would have won every post-war election until 1979. Imagine that!

After the war, the Tories presented themselves as te party that opposed and ended rationing. While this was a clever tactic, what was particularly interesting about their approach was that they framed this as a women's issue. They appealed to mothers, claiming it was thanks to the Tories that they could feed their children, rather than telling men it was thanks to the Tories that they could put petrol in their cars.

Conversely, Labour arguably didn't do enough to champion feminism in and around the 1950s such as by supporting abortion rights reform. However, as Dr Griffin pointed out, this criticism largely leans on the assumption that these were the only issues women cared about. In reality, women certainly did care about a far broader range of policies and issues than men. One could even argue that by focussing on such narrow, assumedly women-only issues such as abortion rights was counter-productive to the feminist movement as there was a still significant gap in how men and women were being treated in politics.

The stark difference between voting behaviour in men and women was not due to a general opinion that overwhelmingly turned women away from Labour. Rather, it was the result of a number of small gaps between the genders on a number of smaller, more specific issues which accumulated into a much larger gap, as we see in the table above.

Finally, Dr Griffin ended by commenting on how much further we have yet to go before we can say we have achieved gender equality in politics. He gave a key example of the 2010 budget cuts which disproportionately negatively impacted women. It was discovered that the government had neglected to carry out the tests it is legally obliged to carry out with regards to what sort of impact the cuts would have on society - and comparing the impact between genders. This kind of attitude of the government is one that has been festering for centuries and which is no longer welcome. There is no question: women are still treated as unequal to men in the world of politics. While such rapid changes did take place throughout the 20th century after decades, or even centuries, of build-up, the corollary of such an explosion of change has meant that the closing of the remaining gender gap will feel much slower. In other words, I have full confidence that we will get to where we need to be. Women will be equal to men.

After such a stimulating talk I was lost for words. It took me a while to collect my thoughts about Dr Griffin's arguments in this talk. My thanks go out to him for causing me to consider arguments and aspects of this period of British political history which I had not properly considered before. Credit also goes to him for the content of this post.

To anyone with the slightest interest in history I could not recommend these masterclasses strongly enough. The Cambridge History Faculty is truly genius and I can't wait for my next opportunity to bear witness to their findings.

If you would like to read more about the 1918 Representation of the People Act, in another post I have argued the importance of this Act, especially in comparison with the 1215 Magna Carta.

Thank you so much for reading! If you would like to be notified when I next upload, feel free to subscribe over on the Home page.

Comments